Who is Venari?

Leigh Hunt

This article originally appeared on The Settlement in June 2019, and was written by the talented author Liz Johnston

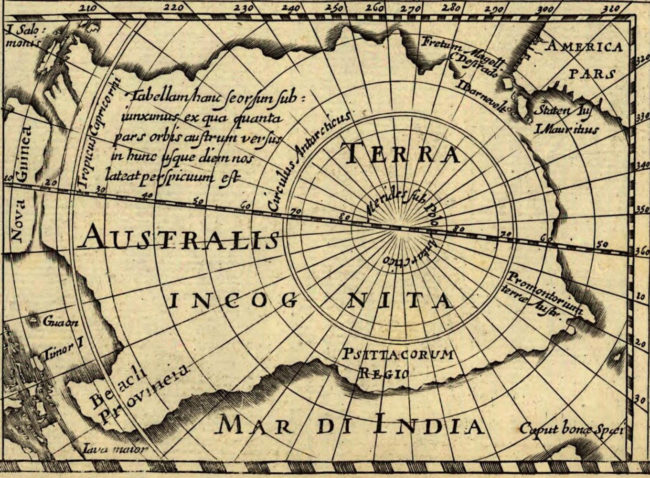

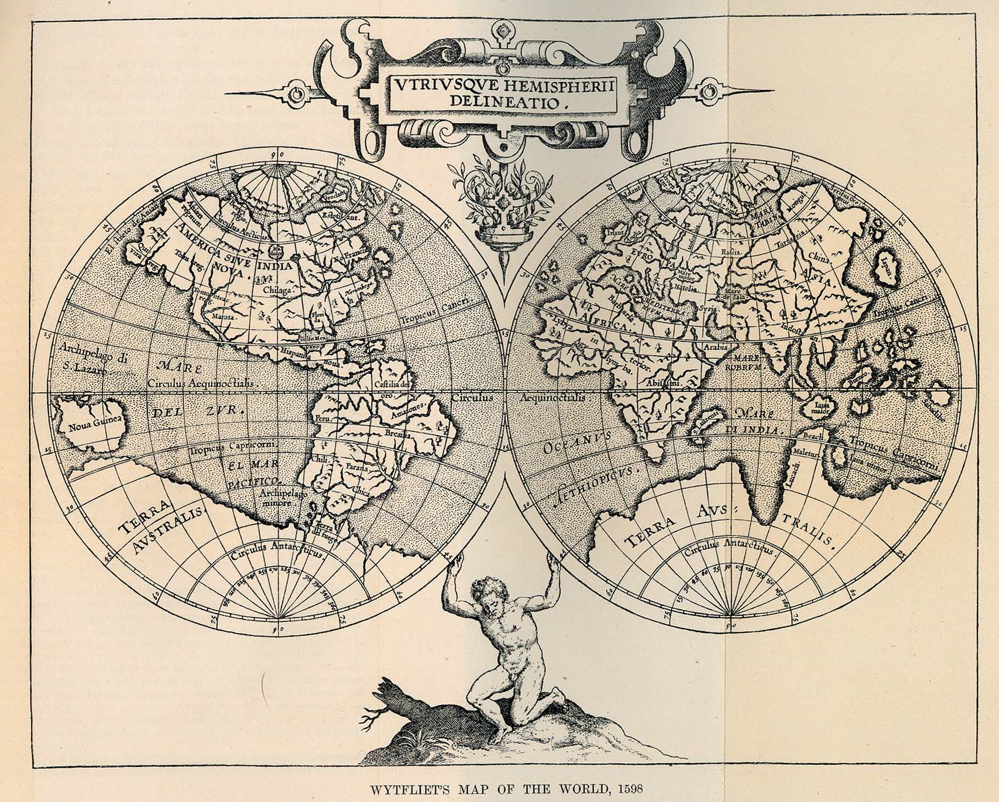

“It’s the edges of the maps that fascinate ...”

In this period of google maps and GPS, we have become entirely reliant upon maps while at the same time unfamiliar with them. Maps today can show by the second traffic changes, give street views down to the minute details, supply a variety of transport options with estimated travel times, amongst so many other things; they give us details about our contemporary societies hitherto unknown to us. They close distances and illuminate the promise of future discoveries. The American street and sculpture artist, Mark Jenkins, stated “Maps encourage boldness. They’re like cryptic love letters. They make anything seem possible”, and it is this allure that drew Porirua resident Leigh Hunt to the wonderful world of maps when he was still a young boy living in England.

Hunt’s interest in maps, and later mapmaking, was sparked by an ordnance survey map he had posted on the wall of his boarding school room, and he quickly found that following established routes and finding new ones was an exciting and engaging way to discover the surrounding countryside. Hunt’s early years of exploration led him to the burgeoning technology industry and the new business of digitally translating and programming data, which in the late 1980s was very much uncharted territory.

Hunt fulfilled a real passion to become part of the Geographic Information System (GIS) field when he started a contract at Laser-Scan in Cambridge in 1998. While still a fairly niche area, it was even more so a few decades ago and it was not until 2000 that Hunt officially began working directly within in the field that had captivated him for so long. Ultimately, what really drives his interest in GIS is the possibility of making sense of spatially related information, effectively conceptualising time and space into a digestible form of representation: maps. His work helps make complex and convoluted data streams comprehensible to the wider public and business owners, and our casual and routine use of map technology today is evidence of the importance and necessity of this innovative contribution! The first project that he was able to fully undertake was working with a team to rewrite the system that produced underwater charts and systems for submarines to prevent them from getting caught in the tides or crashing into marine obstacles and the ocean floor. Certainly an impressive first foray into the expansive arena of digital mapmaking!

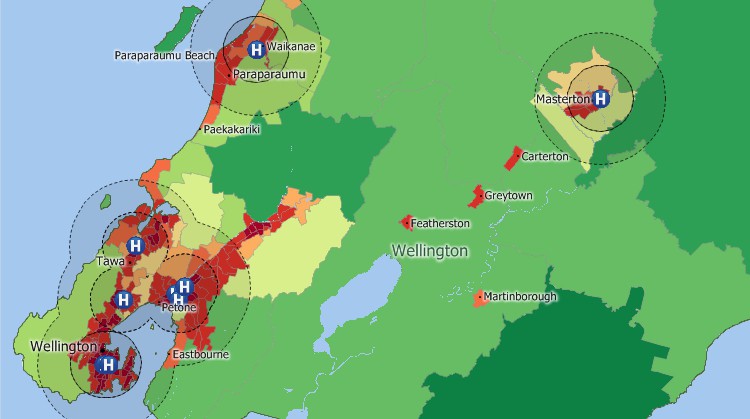

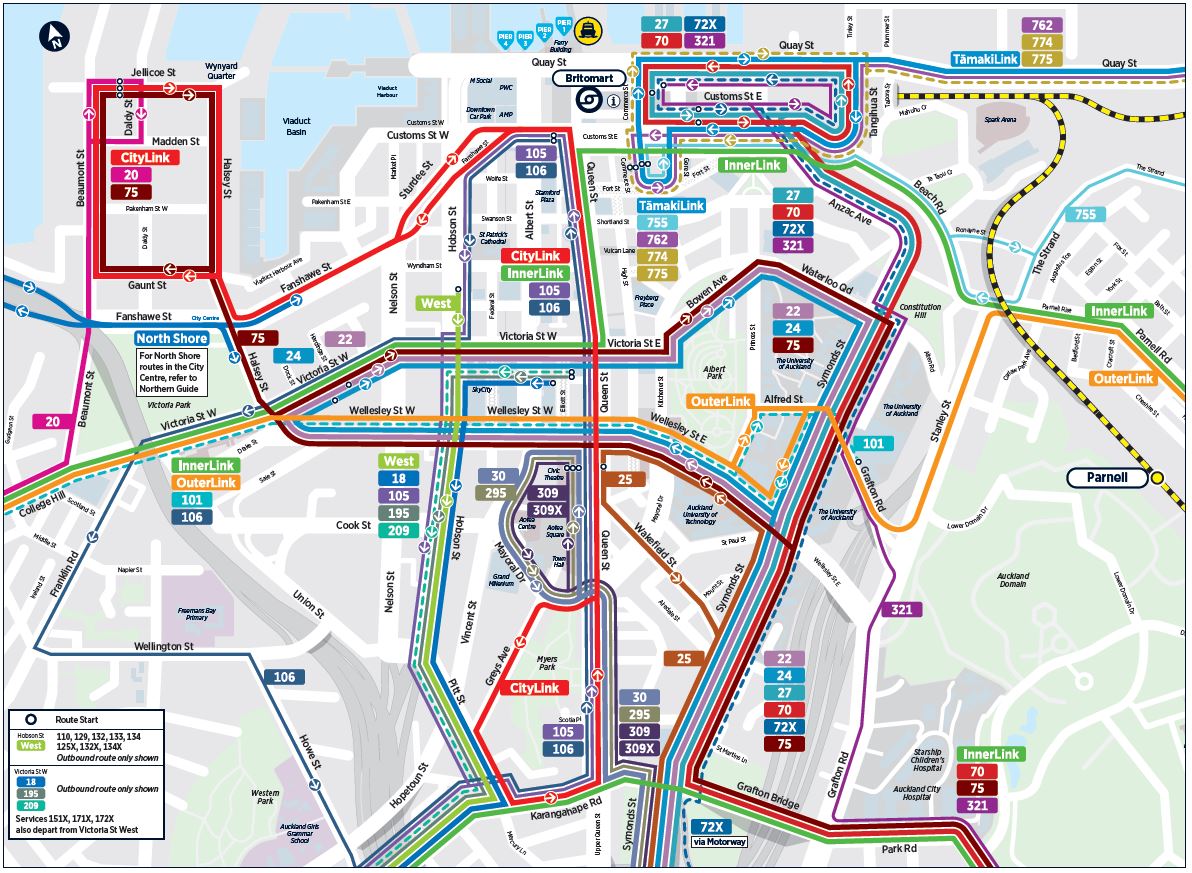

As a child, Hunt lived in various places around the world, including southeast Asia, and he always felt that England was a bit grey and lacklustre in comparison. When he came to New Zealand for a friend’s wedding, he was reminded of how lush, green and sublime the world can be; and so in 2007 Hunt and his family moved to the country that had both entranced and reinvigorated his sense of adventure; and promised a better work/life balance for his wife and kids as well. It was fairly easy making the move to the other side of the world, and like many a transplant before him, he started working in a transitional role before working for a number of GIS companies, landing his current position in 2010/11 with the software development and consultancy company, Venari Ltd. With Venari, Hunt works as a subcontractor for the leading New Zealand GIS group, Eagle Technology (who are the national distributors of the large international GIS supplier, Esri). It is here that Hunt’s interest in the visualization of spatial data has evolved, and his career as a developer specialising in geospatial software has expanded. If it has a spatial component, then you can be sure Hunt is already involved in some capacity! He is currently working on a project for Auckland Transport, designing more accessible and understandable public transit maps, as well as charting the position and duration of ferries in the Auckland harbour. While Eagle has certainly been a place where Hunt has honed his skills and gained valuable experience, his work there does not define him. Like anyone who has a real love for what they do, Hunt has a tendency to become almost too invested in his work. For this reason, moving to The Settlement was a helpful and pragmatic way to gain a bit of distance from Eagle, allowing him the time and space to pursue other interests and accept new and interesting opportunities. We like to think that the flexibility of our office environment mirrors the flexibility of Hunt’s own curiosity! At the moment, he is involved with a semi-secret endeavour to create software for electric vehicles, is working on initiatives to employ drones in mapmaking tasks, and is in the process of restarting his coding programme, CoderDojo Porirua, which helps kids aged 5-17 build robots, design websites and generally have fun with the digital world.

Personal life

As a father of four (a 13 year old girl and three boys aged 11, 9 and 7), Hunt has a pretty busy schedule both at work and home. His wife recently qualified as a music therapist, so there is certainly no shortage of creativity in the family!

Hobbies

- Bicycling! Hunt cycles to work nearly every day from Whitby, which is a solid 18 km round trip each day!

- Drones - he is currently creating 3D maps using drones and exploring the many ways this new technology can assist in more civic-related projects.

- Photography - a long time passion for Hunt, but as you can well imagine he does not have as much time for this as he would like!

- Brewing craft beer - this is one hobby where both the journey and the destination are equally great! Hunt brews beer with some friends, and will be bringing some in for the upcoming beer tasting night here at The Settlement!

I asked Hunt what maps meant to him, to which he replied that as a young child they were the the tool and sidekick to his natural inquisitiveness. He would pick a new spot on the map and chart different routes to arrive at his destination, exploring the many contours of his neighbouring communities in the process. Hunt reminisced that walking in England is far different from New Zealand. Where here the paths and trails are well marked by the DOC, the old winding roads and bridleways of the U.K offer untold possibilities. As a kid, the most fun you can have is going out and getting lost, letting your imagination soar as you embark on a fantastical new life, then find your way home again for dinner and the comforts of family. Hunt found a contemporary outlet to this creative and exploratory impetus with the community driven online resource, OpenStreetMap. It operates in a similar fashion to Wikipedia, in that a solid network of amateur and professional digital mapmakers will contribute code and build upon or alter existing data to better reflect the reality the map is intended to depict. Most recently, Hunt amended the OpenStreetMap of the West Coast to illustrate the erasure of the Waiho Bridge after the flooding in Franz Joseph.

What makes geospatial visualization, or digital mapmaking, so intriguing for Hunt, are the limitations of it. The world is constantly and reliably changing from natural or man made causes, and as such maps, as a representation, are inevitably laced with varying degrees of inaccuracy. Nietzsche has famously stated: “truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are”, and indeed this is valid of maps as well, which we assume as creedence when in fact they are still only an approximation of the thing they are trying to capture. This latent inexactitude leaves room for the unknown, the mystery, the future. As change is the only constant in life, so too are the maps that help us make sense of it. The challenge contemporary GIS developers and programmers face is acknowledging and accepting all the things that they don’t know, that is all the things that they have not put into a map. This realization not only reminds us of our own mortality and limitations, but also helps us find and take the best value from the data that we do have, which has been collated throughout history and is increasing every second. We are well and truly in the information age, with swirling streams of data surrounding us at all times. An unfortunate byproduct of this interconnected, constantly “logged on” world a is the exploitation of user privacy and information, which is something that Hunt and the wider GIS community are incredibly cautious of. With big data comes big responsibility, and the misuse of such knowledge can result in grave consequences if a strict moral code is not followed. What is clear about this incredibly diverse and rapidly advancing technological field, is that we are quickly sailing into the cyber waters of terra incognita, and it’s definitely an exciting place to be. The onus now is to analyze, interpret and map these new discoveries so we can make informed, conscientious decisions and ultimately hold ourselves accountable for what we uncover.